- Home

- Taslima Nasrin

Exile

Exile Read online

TASLIMA NASRIN

EXILE

Translated from the Bengali by Maharghya Chakraborty

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

Preface

1. Forbidden

2. And Then One Day . . .

3. House Arrest

4. Conversations

5. Death Waits Past the Window

6. Exiled

7. Farewell, 22 November 2007

8. Poems from a Safe House

9. Excerpts from a Diary

10. No, Not here! Elsewhere! In Another Land!

Notes

Follow Penguin

Copyright

PENGUIN BOOKS

EXILE

Taslima Nasrin is an eminent writer and secular humanist who has been subjected to forced banishment and multiple fatwas. Her writings have been deemed controversial time and again because of their unflinching preoccupation with gender and communal politics. She has been living in exile since 1994.

Maharghya Chakraborty is a research scholar, an avid cinephile and a translator.

Preface

I wrote Exile nearly five years ago. The book was to be launched at the Kolkata Book Fair in 2011 and my publishers had even organized an event to inaugurate it. However, Chief Minister Mamata Bandyopadhyay had taken a less-than-kind view of the entire thing and had made sure the evening never took off. My name had been prohibited in West Bengal, much like how it had been prohibited in Bangladesh so long ago.

In Exile, I wrote about the series of events leading to my ouster from West Bengal, then Rajasthan and eventually India, my house arrest, and the anxious days I had had to spend in the government safe house, beset by a scheming array of bureaucrats and ministers desperate to see me gone. Without a single political party, social organization or renowned personality by my side, I had been a lone, exiled, dissenting voice up against the entire state machinery with only my wits and determination at my disposal. But there was one thing I was sure of—I hadn’t done anything wrong, so why should I be punished unfairly? Why wouldn’t I, a citizen of the world, be allowed to live in a country I love? Why would a nation that prides itself on being a secular democracy bow down to the diktats of a section of dishonest, misogynist, intolerant zealots, and banish an honest, secular writer?

Despite being forced to leave, I have eventually cocked a snook at all the prohibitions and bans and threats, and come back to India. I have come because I have nothing else but India, and because I hope India will one day truly encourage free thought. I wish to live in this country and be allowed the freedom to express my opinions even if they are contrary to others’. I wish for neighbouring nations to learn from India’s example and be inspired, they who yet do not know the meaning of the freedom of speech. Not that I have a completely stress-free life in India either; the old threats have continued and taken on new forms. Nearly twelve years ago, an imam from Kolkata had set a price of 20,000 rupees for my head, a sum that had soon increased to 50,000 and eventually to an unlimited sum. A director of the Muslim Law Board from Uttar Pradesh had also declared a reward of 500,000 rupees, while an ISIS offshoot from Kerala had put up a post on Facebook calling for my assassination. A leading politician had expressed his ire over whatever I had allegedly written against Islam years ago and declared that I should not be allowed any access to the media to express any views whatsoever on Islam. Everything that I was made to go through—the ban on my book, my exile from West Bengal, stopping my articles from being published in newspapers and journals, stopping the telecast and production of the TV series written by me—was a result of the government’s vote bank politics and blatant appeasement of the fundamentalist elements. A politics built on sycophancy is the first sign of a rotting democracy. Aren’t our political mavericks aware that fanatics seek to plunge society into darkness, that they are against human rights and women’s rights, and that they consider any opinion contrary to theirs a sort of violation?

Writers across the world are being persecuted, whipped, tortured, incarcerated and exiled. But, leave alone dictatorships, even democratic governments are no longer interested in safeguarding the freedom of speech and expression. Whenever I try to point out the significance of such a fundamental right, I am informed that even the freedom of speech must have its limitations and that it cannot be used to hurt someone’s sentiments. Wouldn’t it be extremely difficult to ensure that you never hurt someone’s sentiments? People keep hurting us, intentionally or not, by words or deeds. Our world is populated by a multitude of opposing mindsets. They clash and hurt each other constantly but they also have an inbuilt mechanism to manage hurt. Unfortunately, a few bigots within Islam use the excuse of injured sentiments to cause further mischief, refusing to listen or be placated.

It is a moment of crisis for democracy when a citizen is robbed of their right to speak and express their opinions. Social change makes it necessary that a few feathers will be ruffled and a few egos will be wounded. It hurts people’s sentiments when you try to separate religion and the State, when you attempt to abolish misogynist laws; good things cannot be achieved without hurting religious sentiments. A lot of people had been outraged when the Crown and the State were being forcibly separated in the Continent. Galileo’s and Darwin’s views had upset many pious people of their times. The superstitious are routinely offended by the evolution and advancement of science. If we stop expressing our opinions because someone will be hurt by them, if we curb the growth and development of scientific knowledge, if we forcibly try to stall the march of civilization, we will end up inhabiting a stagnant quagmire, bereft of knowledge and growth. If the objective is to say exactly what everyone would love to listen to, then we would have no need for the freedom of speech and expression. Such rights are important primarily for those whose opinions usually don’t follow the status quo. Freedom of speech is the freedom to say something you might not like to hear. Those who never hurt other’s sentiments do not need the freedom of speech. A State that chooses to side with those who seek to oppose such freedoms, instead of ensuring that they are brought to book, will be responsible for its own eventual annihilation.

Some time back one such draconian law against freedom of speech was abolished by the Government of India. I was among those who had worked towards this goal and our success was a significant acknowledgement of the systematic persecution many have had to go through because of such laws. I have had to face it too, which is why I am glad to have been part of such a reform initiative, despite not being a pure-born citizen of India. The world is constantly vigilant that no one hurts the sentiments of those who are opposed to human rights and women’s rights. When will the world learn to see all as equal? When will it learn to stop pleasing extremists and begin according respect to reason and humanism instead?

This crisis is not India’s alone; it is being felt across the world. It’s not so much a battle between two faiths but a war between two opposing world views—the secular and the fundamentalist, the progressive and the prejudiced, the rational and the superstitious, between awareness and ignorance, freedom and enslavement. In this fight I know whose side I am on; I am forever in favour of my opponents’ freedom of opinion even if I do not wish to support or respect it. My lack of support does not mean that I will attack my opponent during their morning jog, or shoot them in public, or hack them to death. I will neither kiss nor wound my opponent; I will instead express my opinions through my writings. If someone does not like what I have to say, they have the right to respond to my opinions in kind—in words. They do not have the right to kill me. This is a basic condition for the freedom of speech which many fanatics wilfully choose to ignore.

Can faith be sustained thus? There were once so many religions and yet so few exist to this day. Where are the imperious go

ds of the Greeks and where is their Olympus? Where are the powerful deities of the Romans or the exotic divinities of the Egyptian pharaohs? They have been cast into history, just like Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, Judaism and Buddhism too will be forgotten one day, to be replaced by an epoch-appropriate new faith or a rationalist and scientistic outlook.

The terrorists at the Dhaka café were around twenty years old. They were not poor, not illiterate. Heavily indoctrinated in Islam, they shouted ‘Allahu Akbar’ while slaughtering people. Those who could recite a verse from the Quran were spared while others were tortured and hacked to death with machetes. Those terrorists had nothing but religion as their guide. Young men have been brainwashed with Islam, at home, madrasas and mosques. They have been fed the belief that non-believers, non-Muslims and critics of Islam should be exterminated. By killing them, they have been convinced, they will go to heaven. They have also been taught that jihad is mandatory for every Muslim and Muslims should strive to turn Dar-ul-Harb (the Land of the Enemy) into Dar-ul-Islam (the Land of Islam).

There is no point trying to confuse the issue by saying that poverty, frustration, lack of jobs and the absence of hope force people to become terrorists. It is, in fact, the other way around. The new terrorists are often rich and literate, highly qualified professionals, who have been seduced by fanaticism. They join ISIS because they know they will be at liberty to do whatever they wish to, and be given the sanction to rape, kill and torture at will. Many organizations and institutions in Bangladesh have been funded by Islamic fundamentalists from rich Arab countries for decades. Madrasas and mosques have long been breeding grounds for Islamic fundamentalists. Islamization in Bangladesh started not long after its creation in 1971. It is tragic that Bangladesh, whose very birth was premised on secularism and a rejection of the two-nation theory, has degenerated into an Islamic fundamentalist country. The government must own up to an administrative failure to foresee and contain the rise of fanaticism.

In the early 1990s, when I was attacked by Islamic fundamentalists, a fatwa was issued against me, a price set on my head, and hundreds of thousands of Muslim fundamentalists took to the streets demanding my execution; meanwhile, the intellectuals remained silent. The government, instead of cracking down on the fundamentalists, filed a case against me on charges of hurting the religious sentiments of people. I was forced to leave the country and that was the beginning of what today’s Bangladesh is—a medieval and intolerant nation of bigots, extremists and fanatics. Without allowing criticism of Islam, it will be difficult for Muslim countries to separate the State and religion, to make personal laws based on equality, or to have a secular education system. If this does not happen, Muslim countries will forever remain in darkness, breeding and training people indoctrinated by religion to not tolerate any differences, and where women will never enjoy the right to live as complete human beings. People like to believe that Islam is a religion of peace. I, however, have witnessed the opposite since my childhood. The time has come for people to unequivocally tell the truth and be willing to listen to it too. Islam and Islamic fundamentalism don’t have too many differences; Islam isn’t compatible with democracy, human rights, women’s rights, freedom of expression. You will not be able to kill terrorism by killing terrorists. You have to kill its root cause. You have to stop brainwashing children with religion. In the present scenario, a call for sanity and introspection is as good as a cry in the wilderness. This must end. The good and the sensible must break their silence; the inaction of the good is the asset of the malevolent.

This is how the world will continue to endure—ignorance, stupidity and bigotry walking hand in hand with awareness and intelligence. The narrow-minded and the political will forever seek to plunge society into darkness and chaos, while a handful of others will always strive for the betterment of society and to have good sense prevail. It’s always a few special people who seek to bring about change; that is how it has always been.

I hope no one else is exiled for being different ever again. I hope no one ever has to suffer the ignominy I went through. To all the dissidents of the world, my warmest regards.

Taslima Nasrin

October 2016

Forbidden

I have lived in Harvard for almost a year—a rather plaintive, uneventful year, not too terrible but nothing extravagant either. I had, rather impulsively, rented the third floor of the three-storey white house at number 50, Langdon Street, right opposite the Harvard Law School. One could walk from there to the John F. Kennedy School of Government, one of the most renowned schools in Harvard. Or so I had heard, since fame and wealth has seldom attracted me. For me, what has been of the utmost importance are the people—whether they are honest, whether they are good, whether they keep their promises or not.

My office had been set up at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy of the Kennedy School—a small world populated by the computer, the desk, the Internet, the printer, paper, sundry stationery, the sideboard laden with tea, coffee or biscuits, the delicious spread at the cafeteria downstairs, and me with the Harvard identity card hanging around my neck. I used to believe the card held magical qualities. It could open all the hidden doorways and portals of Harvard, allowing me free access to all its nooks and crannies and the secrets they held. It would allow me to get my hands on the rarest of books in the library, stay late into the night in my office, open a bank account in two minutes, or find a magical cure for the most persistent of ailments!

So, I would spend most of the day in my office, occasionally venturing outside to a nearby restaurant for lunch—Indian, American or, if the mood struck, seafood! In the afternoon I would go swimming, or on a walk, strolling past the myriad lives, some neat and some in disarray, laid out around me across the neighbourhood. I fancy that I used to cut an odd adolescent figure as I walked aimlessly in jeans and tops, all fifty kilos of me. I remember Greg Carr, the handsome Harvard fellow who took me to the stadium and explained to me the intricate details of a Harvard versus Brown football match, who wrote so many sweet emails to me, came to see me in my house in a Ferrari and invited me over to his penthouse. Then one fine day, who knows why, all of it had abruptly stopped. Perhaps because I had argued with him over America’s war on Iraq or something like that. I remember how that budding feeling of love had suddenly vanished; the mails and personal calls had abruptly stopped. I have never been good at figuring out the motivations of the rich, but I must confess I will always respect Greg Carr. He had been the one to open the Human Rights Center at Harvard, serving as a perennial reminder that though so many people have the necessary means, few manage to contribute to the service of human rights and dignity.

I would spend my time talking and arguing about a hundred things with the fellows and professors of Harvard, writing my autobiography or essays, composing love letters to lovers I was yet to meet, or writing long research papers, like the one on secularism written while at Harvard. At times I would travel, within the country or elsewhere, Europe sometimes, for a seminar or to collect a prize, or simply to read poetry somewhere; seminars at Tufts and Boston, a speech at the General Assembly of Amnesty International with Mary Robinson, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, poetry-reading sessions at the Harvard Center in Boston with Eve Ensler of The Vagina Monologues fame, helping with the fundraiser of the Women’s Studies Department of Harvard, attending classes by Michael Ignatieff, Samuel Huntington and other renowned visiting academics, discussing the Iraq war with Noam Chomsky in his room in MIT or over email, writing against war, watching the Red Sox at Fenway Park, visiting my friend Steve Lacy who had been battling cancer, debating humanism at the Harvard Chaplaincy, going for soirées at Swanee Hunt’s, or setting off to New York, or to Kolkata for the book fair, before dashing back to Harvard again.

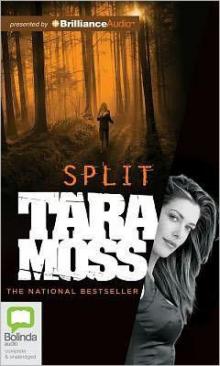

In the meantime, the BBC would, at intervals, keep me updated on the rising tensions in Bangladesh. The third part of my autobiography, Dwikhandito (Split), had been published in Bangladesh as Ko.1 That had been the or

iginal name but the publishers in Kolkata had put their foot down, making me change it. From the moment of publication in Bangladesh, the book had caused an unprecedented furore. I was being abused with the choicest of monikers by the print media—authors and academics had joined ranks in a relentless crusade against my moral character, or lack thereof. I was being called a ‘shameless slut’ because I had named the series of men I had slept with; the pages concerned were being photocopied and handed around as proof of my degeneration. Syed Shamsul Haque2 had once taken me on a trip during which I had developed a rather nuanced understanding of his character; which I had then written about in the book. As far as I was concerned, I saw no reason for him to get upset over this. And yet he was upset and seething like a hyena, primarily because, as the publisher Mesbahuddin informed me, I had written about his secret relationship with his sister-in-law. The big reveal had perhaps been only a sentence long in the entire narrative and yet he was driven to such anger that he filed a defamation suit against me worth ten crore takas. He even gave a series of interviews lamenting how I had ruined his life and reputation, sullied the glorious name he had earned as an author over nearly half a century. He insinuated that there must be a larger reason behind my shameless behaviour, or why else would I dare to write as I had about respected members of the civil society. Inspired to protest, he filed the suit and stated that he hoped others like him, similarly violated by my viciousness, would follow suit and take necessary action against me.

They called me from the BBC to ask for my reaction, and make me aware of the many nasty things Syed Haque and Sunil Gangopadhyay had said about me. How their voices were laced with a scathing melange of anger, disgust, sarcasm and ridicule when speaking about me! I could understand why Shamsul Haque, his secret exposed, might say vicious things about me, scream, spit, swear and cry in anger, and why he might threaten to drag me to the courts in an effort to prove my words to be untrue. However, I could not understand why Sunil Gangopadhyay3 had reacted so violently. There had hardly been anything against him in the book and neither had he ever been a firebrand member of any men’s rights group. In fact, he had maintained time and again that whatever happens between two consenting individuals behind closed doors should never be made public. Isn’t it criminals who cannot reveal their actions to the public? Why should the burden of harbouring criminals always be placed on women!

Shame: A Novel

Shame: A Novel Exile

Exile Lajja

Lajja Split

Split Revenge

Revenge