- Home

- Taslima Nasrin

Revenge

Revenge Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Translator’s Note

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Copyright Page

Translator’s Note

The original Bangla title of this book, Shodh—an elegant-looking word when transliterated into Roman script—hovers in English meaning, I am told, somewhere between the word “revenge” and the idiom “getting even.” I like that balance, and working my way through a basic English translation of Taslima Nasrin’s novel, I sought to render an equivalent one between the heroine’s suffering and the author’s witty feminist commentary on the cruelty of her character’s situation. In doing so, I came to understand Revenge as a fable—that is, a cautionary tale in which the reader’s sense of what is “natural” is challenged.

Take one of the most familiar of Aesop’s fables: A tortoise challenges a hare to a race, and the hare accepts, assuming, as we do, that he will beat the tortoise, a creature slow by nature. The impartial fox sets the distance, and the two set off. The tortoise never stops, but the confident hare soon tires and stops by the side of the road to take a nap. He wakes to find that the tortoise has passed the finish line. Slow and steady wins the race, as the saying goes.

Like a fable, the tale you are about to read is a metaphorical narrative, and offers a warning. So as not to give the end away, I won’t say what the warning is, but as you enter this story, remember that there are still places in the world where a woman with a physics degree is asked to use it only to boil water, and that even in the West, there are marriages in which a husband’s jealousy creates a wife’s reality. It is the brilliance of Taslima Nasrin’s narrative that the constrictions of sexism she realistically depicts strain credulity as fiercely as the obstacles in any fable. Like Aesop’s tortoise, or, if you prefer, like a Jane Austen heroine, Nasrin’s Jhumur employs wit and simple logic to get even, and in so doing changes her life and earns a place in the great tradition of clever fictional women.

—Honor Moore

June 2010

1

It’s dawn and again my stomach is turning, an alien taste spiraling up through me until I feel it on my tongue, a sour dribble flooding my mouth. I make an effort to hold it down, but it keeps rising as if to taunt me. I run to the bathroom, squat at the toilet, and vomit. All day everything sways as I read, cook, or simply stand, hardly able to remember who or where I am. And then I sit or lie down. That’s how it’s been now, for four days.

Haroon of course hasn’t noticed. Even this morning when I approached, a smile curving at the corners of my mouth, and told him I had symptoms of what is surely morning sickness, his eyes remained riveted to the mirror, his fingers busy knotting his tie. I had imagined he would sweep me into his arms and kiss me, or dance me across our bedroom wild with joy, as I had once seen an exultant Dipu whirl Shipra around a dance floor, as if they wished to live a thousand years. When Dipu released her from his arms, Shipra took me aside. She had morning sickness and her beloved husband was in such a state of happiness he’d missed work and they’d spent the whole day alone, celebrating. A husband and wife falling all over each other with happiness! How charming!

But my beloved Haroon kept fussing at his tie. I wondered if he was so inept at achieving a Windsor knot that he couldn’t hear what I was telling him, couldn’t see my face, my open staring eyes. Nothing I could do broke his concentration. I watched as he inventoried the lunch in his tiffin box for hard-boiled egg, bread and apple, then slid it into his briefcase. And then I watched as he put on his shoes. I’d never seen him so rapt! Not waiting for him to finish, I repeated my happy news, but he neither looked at me nor responded. When he hesitated at the door, I had a flash of hope. Maybe he’ll turn and tell me to get dressed for a day on the town, call his office to say he won’t be in. “This, my darling, is no ordinary day,” I imagined him saying, taking me in his arms. And then we’d broadcast the news to his family and spend the day imagining what to name our first child. Why shouldn’t my husband be like Shipra’s?

Haroon did none of these things. Once he’d tied his shoes, he picked up his briefcase, and headed to the door. The little smile was gone from the corners of my lips. It wasn’t normal for a woman to vomit so early in the morning. I raised my voice so he’d be sure to hear. “Can’t you see what’s happening to me?” But Haroon kept his eyes on the door, as he answered, “There are some Pepto-Bismol tablets in the cupboard, take them!” I could barely hear him for the image of Dipu and Shipra dancing before my eyes.

“What did you say?” I wanted to be sure Haroon actually understood that I had morning sickness, that he didn’t think I was simply down with stomach flu. I wanted to give him a chance to revise his cruel response, to clear his mind, so that he would know what lay in our future, so that he would offer me something other than a pill.

But instead, he slipped through the door, leaving it slightly ajar so I could see him as he walked down the stairs and disappeared. I picked up after him and then set about finishing the kitchen chores just like an ordinary woman. I had been warned never to call after my husband when his back was turned, that doing so was inauspicious, and so I followed tradition, reining in my impulse to shout after him, holding my tongue so as not to bring him harm.

There was, as always, plenty of work: preparing breakfast for everyone, baking the roti that Rosuni, the maid, had rolled out. She was an especially skilled cook, but the family preferred to have me actually produce the meal—another tradition established to prove the worth of a daughter-in-law. And so, even though Rosuni was perfectly capable of it, I chose whether we ate fried eggs or vegetables with our rotis, and thus, everyone was happy, which made Haroon happy. For the six weeks we’d been married, I’d gratified him by preparing meals three times a day, doing all the washing, and taking care of the house, not once allowing the scarf to slip from my head.

But this morning, I fled the kitchen for my bedroom, shutting the door behind me, lay on the bed, arms and legs spread, knowing full well that I ought not to be flouting my duties. But what was I to do? Rosuni was kneading the dough, but I could not stop the churning in my stomach, the rising force in my belly, and the moaning that came whether I wanted it or not.

As I lay there, the beatific expression on Shipra’s happy face sailed across my vision, waves of envy breaking on a tiny beach at the back of my consciousness. What was it that had brought Dipu’s arms to embrace her, while my news had produced nothing but a pinched look on Haroon’s face and the stingy offer of a pill or two? Was my dear Shipra more intelligent than I was, more skillful in the mysteries of love? Even my sworn enemy would agree that I was not one but two notches above my beloved best friend in beauty and talent. Shipra had dropped out of university after a year to marry Dipu. Acquiring pots and pans and every piece of necessary furniture with the perseverance of an ant, she made a home in no time. I too had married for love! And I, too, was living every day and hour in compliance with my husband’s wishes, neglecting none of my wifely obligations either in the bed or at the stove! So why, I moaned, why does Shipra get such ebullient love? I couldn’t fathom the reason and I couldn’t keep myself from weeping.

When Shipra was ready to deliver, Dipu took her to a clinic in Gulshan, despite the fact that his family had wanted him to take her to a government hospital to avoid “unnecessary expenditure

.” But Dipu was no fool. He knew that proper medical care was not always forthcoming in government hospitals, that one might wait indefinitely for a free bed, that a patient might even find herself giving birth on the floor. Nothing was too good for his Shipra or their child. Dipu did not have the money himself, but he did not hesitate to borrow from his friends.

When I visited Shipra at the clinic before she gave birth, Dipu was always there—fussing over her medication and diet, pouring her fruit juice when she was thirsty. I could barely get close to her! If Dipu wasn’t ruffling her hair, he was rubbing his nose against her belly, mumbling endearments: “How is my little one doing in there?” Doctors raised their eyebrows and a nurse, winking, remarked that in her experience fathers were apt to panic rather than purr at the birth of a first child. How I envied my friend, even secretly wishing Shipra and I could change places. If only I were the mother soon to give birth, the woman whose husband was lavishing all this attention!

Again, my stomach churned and again I rushed to the toilet to vomit. No one—not Haroon, nor his Ma, not his brothers or their wives and sisters—no one was willing to acknowledge something was happening to me! That this was the fourth day I’d woken up retching, that my world was lurching, and that, in all likelihood I was pregnant. I pulled myself up from my knees and opened the bathroom door, and there was Rosuni.

I guessed why she was there. It was time for breakfast, and soon the family would want a breakfast cooked by the bou, me, the lovely daughter-in-law. But the rotis were not ready, and I was not going to the kitchen that day. Rosuni was the first in the house to notice that something was wrong. She would make the rotis, she said, fry the eggs, and serve everyone exactly as I would. I smiled my thanks and, with relief, threw myself again onto the bed. Soon the sun was blazing through the curtains, scalding my skin, but I didn’t care how hot it was, just as long as I could see the sky. So many days, sitting at that window after hours of housework, I’d gazed upward at the azure strip of sky, wishing I were a bird taking flight. If I were robbed of that image of freedom, I thought to myself, I’d be left with nothing.

Some evenings, as a night breeze swept the balcony outside our room, I’d stand longing for a glimpse of the streets crowded with people and moving vehicles, but tall buildings blocked the view, and I could never see beyond the narrow strip of garden. Once in Ranu and Hasan’s room, which has a view of the street, I was standing looking out the window when Amma, my mother-in-law walked in, “It doesn’t become a housewife to stare at people,” she said sternly. “Step back Jhumar, or the neighbors will talk.” Of course she reported the incident to Haroon, who quickly sided with her. “You have no sense at all. You forget you are the daughter-in-law, the bou of this house.”

My dear husband couldn’t have been more wrong! I knew I was the bou of the house only too well. I didn’t dare think otherwise even for a second. I knew that the moment I entered the house I had to reduce my voice to a murmur and keep my eyes lowered, fixed to the ground, so I wouldn’t meet the eyes of any other person. How else could I succeed at being Haroon’s perfect, self-effacing wife! I’d learned the requirements the day of my marriage when I’d laughed out loud at Haroon’s younger brother, Habib, prancing about the house with a cap on his head, and Haroon had come running. “What on earth are you up to? Why are you making such a racket?”

“I was just laughing,” I said.

“Don’t you know that the people next door can hear you?” What was he thinking? Hadn’t I always laughed like that? Hadn’t my gaiety prompted him to remark more than once that my sense of humor was what he liked most about me?

“Just laughing?” he said.

“Yes,” I said. “Just laughing.”

“It’s not wrong to laugh,” he said, “but you mustn’t laugh so loud. You sound like a man!”

Not only did he now disapprove of my laughter, he was at pains to track whatever else I did. Had my head been covered when I stood out on the balcony? He was horrified when I said I couldn’t remember. “What will our neighbors think?” he snapped, sounding for all the world like a mother-in-law. “Have you ever seen women staring from those balconies?” he asked, pointing to the apartment building across the courtyard. “A good woman stays indoors,” he said. “The more hidden a bou, the better her reputation.”

So, I would not stand again on the family balcony. Truly, until that moment, I’d had no idea that people in Dhanmundi worried about women on balconies. I’d expected as much in Wari, where my parents lived. In that overcrowded old neighborhood, people poked their noses into the affairs of others twenty-four hours a day. But here, in the heart of the city?

It became a mystery to me what had happened to the man who had courted me. One day, soon after Shipra gave birth, I asked to visit her at the clinic. Haroon raised his eyebrows in surprise. “Why Shipra?”

“Because she is my friend and she’s just had a child, and I have given the child her name.”

Haroon refused.

“Your life has changed, Jhumar,” he said, with a smile on his face I hardly recognized. “Your new life must bear no traces of the old.”

“What has happened to you?” I asked him. “I barely recognize you.”

“Why can’t you figure it out? You are now Mrs. Haroon Ur Rashid, bhabi to Hasan, Habib and Dolon. Your address is Dhanmundi not Wari and you no longer carry your old name. It is not proper for my wife to gallivant the entire day! You are the elder bou of the house.”

Bou indeed, I thought. I remembered the days before we married, the two of us adventuring for days on end and into the night, traveling outside the city. We had walked village pathways and watched the sun drop into the Kansa river, and, sitting on a rocky mount one evening, had watched the stars. I remember Haroon that night. “I want to go through my entire life like this!” he said, his eyes bright, full of love. “I want to talk deeply with you, about the mysteries of existence.” I could hardly believe my good fortune. “I hate the struggle of business, the idea of running a household. Oh Jhumar . . . ” He seemed never to have his fill. “Why has the day gone so suddenly?” he would exclaim. I too wanted to stretch time. How I looked forward to married life, when the days would extend to weeks in a new life together.

But it was as if the wedding wine had transformed my beloved companion. Dreamy Haroon overnight became someone I did not know. “Work is all there is to life,” he would say, standing in front of the mirror, adjusting his jacket. Suddenly he was a cartoon of the working stiff. “One cannot reach the top of the ladder of success unless one works,” he’d say, smiling cooly, the door closing behind him, leaving me to hours of loneliness. Gone was my stargazing suitor. Now he was tied to a nine-to-five routine. If I suggested he take a day off, it was as if I’d spoken to him in foreign language. “I cannot afford to lose the money. Those days before the wedding have already cost me.”

“Have we no need for each other,” I asked him, “just because we are married?”

“My darling, I can have you whenever I want! I know you’ll be there when I get home.”

Now Rosuni was in my room and, closing the door, she pulled the curtain back. The sun poured down my back. “Bhabi, come and have breakfast,” she whispered.

“I’m not well, please go away . . . ”

She drew close and speaking in a hushed voice asked what was wrong. Her quiet tone reminded me of my precarious position. Even a servant did not want to be caught gossiping with a woman who was failing at her duty. Those with more authority were allowed to be indisposed, but the bou had to remain forever healthy. How could she be in a sickbed if someone else got a fever? Rosuni couldn’t be seen chitchatting with such a slacker, even if she felt compassion. She had been a bou once, constrained to stay in good shape; I could see she understood the drill, her eyes darting toward the door as she made me comfortable, pulling the curtain closed again so I could rest in the shade. I felt a surge of gratitude—in a sense Rosuni and I, maid and bou, were in the same boat. Even thou

gh a gulf separated us socially, we did the same work—she cooked and so did I, she tidied up, but so did I. As she moved quietly in the half-darkness, I watched her with something approaching envy. She could remove her head scarf whenever she pleased; I had to keep my head covered whether I liked it or not.

I had barely a second for this reverie before Amma burst into the room. Why was Rosuni gossiping with me, shirking her work? “But Madam,” Rosuni said quietly, “Hasan is asleep, Habib is out of the house and Ranu is knitting a blanket.” She had come to persuade Miss Jhumar to eat. Amma felt my forehead and declared I did not have a fever; Rosuni quickly covered her head and made for the door.

It was past ten o’clock and I was still in bed, but Amma had no sympathy for how I felt. It annoyed her that I wasn’t in the kitchen, if not cooking then at least supervising the afternoon meal. Slowly I got up. “I may not have a fever, Amma, but I have a headache and I’m sick to my stomach.”

“Headache!” She suffered from it often. “Dousing your head with cold water will banish it soon enough!” she exclaimed. She felt nothing for me I was sure, but I took her advice, making my way to the bathroom to splash some water on my face and neck. I knew she was concerned about Dolon, Haroon’s younger sister, whose husband had lost his tobacco company job and was sitting at home. If only Haroon could spare some money and set his brother-in-law up in business, then Dolon could have some peace.

And she was always worried about her other two sons. Hasan, the older one, had dropped out after high school, and Habib had completed his university matriculation only for appearance’s sake. Hasan, now living at home, content to eat whatever was set before him, never worried his head over household matters, but a few weeks ago he had appalled us all, producing a thirteen-year-old girl in a red sari whom he proclaimed his wife! The girl, Ranu, was weeping, wiping her tears with a white handkerchief, the red from her lips running down her chin. Who was she? We all wanted to know. And where had Hasan found her? Was she a gentleman’s daughter he had kidnapped, or a novice hooker from the red light district?

Shame: A Novel

Shame: A Novel Exile

Exile Lajja

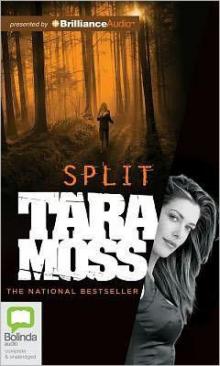

Lajja Split

Split Revenge

Revenge