- Home

- Taslima Nasrin

Split Page 4

Split Read online

Page 4

His face would be a mask of fear, dread clouding his eyes all the time. Geeta’s terror loomed over him like a shadow. At Abakash whenever he refused to eat we used to tell him stories to entice him. With Geeta he was not allowed to touch any food even if he were to die of hunger. There would be food in the refrigerator and on the table but he had strict instructions not to lay a finger on anything. He was only allowed to eat when Geeta would feed him—bad, often rotten, stale and inedible food. We saw him grow skeletal gradually, his plump, cherubic frame withering under her onslaught. At least when Chotda used to be home he would gather everyone at the dinner table for meals and Geeta would have to feed him meat and other things despite her reluctance. Before outsiders she maintained the perfect maternal facade, her love for her son shining forth bright, but few remained unaware of her conniving nature for too long. Geeta was a cunning woman; she could hide her true vicious nature all too well beneath layers of affect to be able to manipulate and control anyone for her own gains. However, none of the relationships stood the test of time; she would be gone like the wind as soon as her purpose was served.

Unable to stay away we would go back to Nayapaltan time and again just for a fleeting glance of Suhrid. Mother would take chicken for him and lots of fruits, but Geeta would take everything from her and hide it all away, not breathing a word about it to Suhrid. Earlier, as soon I got my salary I used to take him out and buy him the toys he wanted. I continued doing so, buying clothes and toys and taking them to Dhaka, but the same thing happened and Geeta would lock everything away in the cupboard, neither telling him nor giving him anything. She instead gave everything to Parama, who had her sole attention. The love and care Suhrid used to get at Abakash was now reserved for her daughter. The little girl even had the right to abuse her older brother, hit him or kick him and he had to endure it all silently. The two siblings were being brought up in different ways in the same house. Suhrid had never taken showers on his own; instead, Mother used to bathe him with soap and lukewarm water, massage him with olive oil and comb his hair neatly. Living in Dhaka he had to learn to bathe on his own; most days he would just pour some water over his head and come out. Geeta would bathe Parama, give her new clothes, shoes and toys, reserving the old hand-me-downs for Suhrid. He had a hard mattress to sleep on while Parama got a soft bed. She got the kisses while the blows were for him. Geeta would rub baby lotion on the girl, comb her hair, and coo, ‘Do you want some grapes, princess?’

‘No.’

‘Please, just a little.’

‘No.’

‘My little darling, please, only a little.’

The girl would nod in acceptance. Immediately Geeta would yell for Suhrid to fetch Parama grapes. Suhrid would run to obey his mother.

He would ask, ‘Can I have some too, Mother?’

‘No!’ she would bark. Or perhaps Parama wanted to put on her shoes. Geeta would call, ‘Suhrid, get her shoes.’ He would get the shoes and be rewarded with a blow on his back. ‘Go clean them first!’ Geeta would bark again. Then she would say, ‘Go put them on her feet.’ If he were to complain, ‘Am I her slave?’ Geeta would instantly lunge at him, brandishing her slippers and beating him, and scream, ‘Yes, you are her slave. You help her wear them every other day so how dare you complain today? What is making you so brave? Who? Do you think anyone will be able to save you from me?’ All this would happen in front of me and unable to bear it I would leave the room to go to the balcony and cry, struggling believe the scene I had witnessed with my own eyes. Could a mother ever behave in such a manner with her own child? I have often heard stories of evil stepmothers but all such tales paled in comparison to how Geeta used to behave. Mother used to say, ‘She didn’t clean his shit or his piss, nor did she teach him to walk or talk. She got a tailor-made son after six years, so of course there is no attachment.’ I have always wondered why, though. Do mothers who have been reunited with their children after many years of separation love them less intensely? Father would visit Suhrid too and Geeta would not let him meet the boy either. He would struggle, wanting to come near Father but would be restrained with punches, slaps and dire warnings. Each time Father would return to Abakash broken-hearted—‘Has Geeta completely forgotten that Suhrid is her own child?’

~

After each visit we returned from Dhaka, with our hearts heavy and distressed about what was happening right in front of us. It often happened that we would turn up at Nayapaltan but Geeta would not open the door to let us in. Once, braving a terrible heat wave, Mother went to Nayapaltan, enduring the dust and the soot of the unruly and crowded bus from Mymensingh to Dhaka, only to end up waiting in front of their door for nearly four hours before returning home. Geeta had been at home that day but she had refused to open the door. Another time Suhrid had seen Mother through the window and called out to Geeta to open the door, but she had not responded. Suhrid had dragged a chair to the door all by himself and unlatched the door. Obviously, for this act of defiance there had been severe consequences for him over the next few days. On many an occasion I too had to return from Dhaka empty-handed. Even if Geeta were to open the door she would not tell us to sit or offer us any food. We usually got food from outside and spent the night on the couch, only for Suhrid. Often we thought to simply stop going, only to change our minds later—we kept going because of Suhrid, because our visits never failed to make him happy.

To ensure our visits continued unimpeded we showered Geeta with gifts so it would appear we loved her dearly, took the entire family out to the restaurant, or the theatre, and to fairs and markets, wherever she wanted to go, as if she was the kindest person in the entire world. We tried hard to make sure she did not sense that we were doing everything only for Suhrid’s sake, so that he would be allowed to meet us and to ensure he had some respite from his otherwise suffocating existence. Geeta understood everything, of course, and I knew that she did. She never said anything, neither did she let Suhrid sense anything. It often happened that I would leave my purse stuffed with money in the living room to go to the toilet, only to find it empty when I returned. The same happened to the earrings I once took off before going for a shower. I was sure about one thing—if such things made Geeta happy then I was fine with letting this continue just so she would refrain from thinking of new ways of tormenting Suhrid. I regretted my losses in silence and did not utter a word aloud. We had to flatter Parama too, pick her up and coo about her prettiness when she was anything but, besides giving her gifts because it made Geeta happy. If Geeta was happy she would ask us to sit or even let us meet Suhrid, at the very least let us have a glimpse of him or a moment of respite when he could quickly come and touch us. Even a fleeting touch was very important to him. Geeta’s mother and siblings would often stay over with them and I saw them fawn over Parama and abuse Suhrid as well. Making Geeta happy was obviously her family’s primary economic necessity.

This one time Suhrid fell and broke his hand and Geeta refused to take him to a doctor; in the end I had to. The doctor took an X-ray and detected a broken bone. Suhrid’s hand was put in a plaster and placed in a sling, with the doctor warning us that it would take nearly a month to heal completely. No sooner had we returned to their place than Geeta tore open the plaster and sling and declared, ‘Nothing’s happened to him. It’s all an act.’ We tolerated everything Geeta did, all the time praying that she would direct her ire at us and not him. Suhrid too understood everything and the six-year-old endured all her cruelty so she would not misbehave with us. Quashing all his emotions and natural exuberance ruthlessly he picked up lessons in deviousness. He tried his best to make his mother happy, say things that pleased her; he learnt to put on an act simply to gain some sympathy from his own mother.

Chotda would return from his job in the airlines every two weeks or so. As soon as he entered Geeta’s complaints would begin—Suhrid was bad, he never listened to anything she said, there were complaints against him from school, he had hit Parama, and more such figments of her

imagination. She was happy when Chotda scolded Suhrid; she encouraged him to fawn over Parama instead, placing her in his lap and praising her to the skies—Parama was good in studies and in recitation, skilful at games as well as taking over people’s lives, and so on and so forth. There was no end to things she wanted, especially since everything was about her. Chotda did notice that Suhrid was being mistreated but he did not possess the courage to stand up to Geeta. He gave all his money to her and it was his duty to follow everything she decreed—not just Suhrid, Chotda too was terrified of her. Geeta had long since resigned from her job as a receptionist in the airlines office and transitioned to being a full-time housewife. It was not as if she led the life of a housewife, though—she had a swanky lifestyle, she drove her own car and went where she pleased, to play tennis or swim. Despite being a housewife Geeta led the sort of independent lifestyle that most independent and affluent working women could only dream of. Her fearlessness and self-assurance used to amaze me while her lack of generosity, her cruelty and her misbehaviour troubled me as much.

Mother was worried that all this would affect Suhrid’s brain, since he was not getting a chance to have a normal childhood. She also believed Geeta would eventually begin to love the boy. In fact, we believed that too, but we were foolish in thinking so. At the very centre of it all there was one reason why she hated Suhrid—she hated him because he did not love her, he loved us. That love had not diminished an ounce even after they had separated him from us; this realization further stoked her rage. Her envy, her obstinacy and her pettiness had stamped out every last bit of common sense.

It happened that we went months without visiting Suhrid, only to give their relationship a chance to become normal and to ensure Suhrid got a chance at growing up like any other child of his age. Whenever Chotda came to Abakash with them during Eid Suhrid would come back to life. He brightened up at once, playing, running, laughing and crying like before simply because we were near him again. All this would change in an instant if Geeta was around. It was the same every Eid; he refused to go back to Dhaka with them at the end of the day. He would go and hide, trembling in fear. They always found him in the end and beat him into submission, dragging him to the car. His screams of pain while being dragged away left scars on Abakash and the entire neighbourhood.

Geeta could never love Suhrid and neither could Suhrid ever love his mother.

~

Without Suhrid, for long stretches of time Abakash remained lifeless, a ghostly fortress that once used to be full of laughter and joy. For days on end there would be nothing to keep us company but the silent sighs emanating from the spectral house.

I Could Never Touch You

The ashes of an incredible dream—a life with R, a life for the two of us together—clung to me like skin. I knew it was no longer possible to live with him; I was well aware that we had both definitively turned towards different lives away from each other. That the time had come to clean the ash and grit off and start afresh. Yet time rolled by, the days burnt out silently, the nights kept howling by like monitors shrieking in the dark, and I remained stuck all by myself like wreckage cast aside. I could not fathom which new direction I should choose, which way I should go where his crushing absence would not immediately set off after me like a maniac in pursuit. Life felt like a feather at one moment and heavy as a stone the very next. I had never really felt this weight before, the full weight of life, and before I could make sense of things it had crept down my back and slowly bent my spine. I could not recognize this life; it was mine and yet it was not. Without pausing to consider I had given away everything life had offered to me to another. Later, racked with thirst, I had reached out and found that there was nothing left for me.

My life was spread out in front of me like an arid wasteland. Every day I would run to the door on hearing the postman—like I used to previously, but not exactly like that either—despite knowing for certain there would be no letters for me. I searched among the pile for the one letter whose words magically arise from the page and dance like dreams in front of my eyes, their silvery shimmer falling on me like rain. I knew I would receive no letters like I used to once but the desire buried deep inside me would frequently resurface without warning, like a boisterous gaggle of adolescent girls. It was not me; rather it was some other entity inside me, searching for a familiar handwriting on the envelopes. It was not me; it was someone else who sighed when there was no letter to be found. Every day I would stare after the departing back of the postman, the letters he had left behind in my hand, the sighs surrounding me. Not mine, someone else’s. I tried casting this unknown person aside, struggled to keep the entity hidden in some dark dungeon deep within. Every day, over and over, I tried to forget that I would never get another letter from R. On my knees in the ash I helplessly sat searching, hoping to unearth even a few shards of the incredible dream that might have been left behind by mistake.

Come February, every afternoon I ran into many poets and writers while strolling down the book fair on the grounds of the Bangla Academy in Dhaka. Many conversations, many hours spent in the tea stalls over adda, although through it all my eyes searched tirelessly for one particular face and a familiar pair of eyes. Every night I returned home unfulfilled. Then suddenly there he was one day and I found myself walking up to him, my feet driven by some unrecognizable part of me. I wanted to ask him, ‘Are you well? If you are, will you tell me how? I have not been well. You seem happy. How do you seem happy? I have not been happy for a long, long time.’ I said nothing as he stood there surrounded by friends. Instead, I quietly watched him for a long time, wanting to break through the barrier to go stand in front of him and stroll through the book fair with him like we used to. I turned my desires over in my mind, played hide-and-seek with them a little, blindfolding them and running away. And then, safely at a distance, I would stop to turn around and laugh, the laughter ringing out like a hollow wail even to my ears.

His new book of poems was out but I could be a part of the joyous celebrations only from a distance. When I did manage to buy his book Diyechile Shokol Akash (You Had Given Me All the Sky) and approach him for an autograph he stared at me coldly for a while before scribbling on the front page—‘To Anyone’. Somewhere down the line I had become just like anyone to him. I stood there numb with the book in my hand, and I could feel my thoughts pounding in my head like a tribe of monkeys trying to tear me apart. Had R known how much I had hoped he would ask about me? How was I, when did I reach Dhaka, how long was I going to stay, and more. All my acquaintances had asked me these questions. Were R and I not even acquaintances any more? How could he be so thoughtless? Could someone forget a person they once loved so soon? Riding pillion on my desires the unanswered questions returned home with me.

Towards the end of the book fair we finally managed to talk, sit down and have tea together. I asked him about his leg and he told me he was finally able to walk short distances.

‘Did you stop smoking?’

‘That will be quite impossible,’ he laughed and replied. I did not ask if he had managed to quit other things too, afraid he was going to say those would be quite impossible to quit too. Gazing intently into my eyes for a while he asked me in a deep voice, ‘Come with me to Jhinaidaha tomorrow, early in the morning.’ He did not know if I wanted to go nor did he wish to; he asked me as if he still had the right to ask me, as if he knew I would agree. As if the moment he touched me I would cry out like a stubborn girl. I was supposed to return to Mymensingh the day after and there I was being offered a trip to Jhinaidaha instead. There was a poetry event being organized there and other poets were going to attend as well. The last time, when our separation had not yet been finalized, we had gone to Cox’s Bazar where we had bathed in the sea and read out poetry to each other on the beach in the twilight. The poets Mahadev Saha and Nasir Ahmed had been there too—Saha in a lungi and a kurta with a gamchha over his shoulder, R and Nasir Ahmed in long trousers and me in a kangaroo-yellow tee and j

eans. We had waded into the sea, our clothes had gotten wet and heavy and the waves had tried to draw us further in over and over again. It had been wonderful! I decided to go to Jhinaidaha, not to be a part of the celebration but only because I wanted to be with R. We were divorced, we were no longer in a domestic partnership, but there was no one closer to me in the world than R and there was no greater friend. We had grown close over many years and he had become my entire world. He had hurt me but I could not deny that I still loved him.

There was a bus for Jhinaidaha from the Bangla Academy. On the way we spoke about the smallest incidents and accidents that had happened in our lives in the meantime. The only thing I hid was my pain, never telling him how in the cold mornings I usually awoke to a frozen lifelessness. Suddenly he asked, ‘You want to listen to a poem?’ Was it even possible that I would turn down one of my favourite poets? Sitting beside me in the bus R read the poem out aloud—it was called ‘Dure achho dure’ (The farthest you are from me).

I could never touch you, the part which makes you, you—

I have sifted through warm bodies in search of happiness,

We have dug into each other in search of solitude,

But I have never been able to touch you.

The way they break oysters to find pearls,

You have only found disease in me,

Shame: A Novel

Shame: A Novel Exile

Exile Lajja

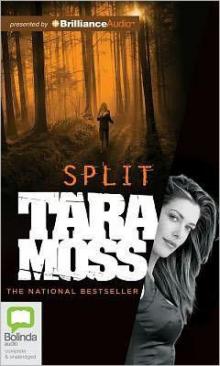

Lajja Split

Split Revenge

Revenge